Why Did Edwardian Women Wear The Hobble Skirt?

A Fashion Trend or a Fashion Trap?

The hobble skirt, designed by the visionary French couturier Paul Poiret in 1910, became one of the most memorable, if controversial, fashion statements of the Edwardian era. This garment, with its impossibly narrow hemline, did more than just change the way women dressed—it turned their very movements into a public spectacle. As the name suggests, the hobble skirt restricted a woman's stride so severely that walking became a delicate balancing act, almost akin to a slow, restrained shuffle. It's as if Poiret, with a mischievous glint in his eye, decided to literally tie the legs of fashion-forward women together, leaving them to hobble about like Victorian ladies in a three-legged race.

Hobble, Hobble, Toil and Wobble. Editorial from The Tatler, September 14, 1910.

But why would anyone willingly don such a restrictive garment? The answer lies partly in the zeitgeist of the time. The hobble skirt emerged during the suffragette movement, a time when women were vigorously fighting for their rights and, quite literally, their freedom of movement. Some speculate that Poiret’s design was a satirical commentary on the patriarchy’s attempts to limit women's progress, a sartorial ball-and-chain to keep them from marching too quickly towards emancipation. Whether Poiret intended this or not, the irony wasn’t lost on the public. Newspapers and magazines had a field day with the hobble skirt, with cartoons, poems, and satirical articles portraying it as the fashion equivalent of a medieval torture device.

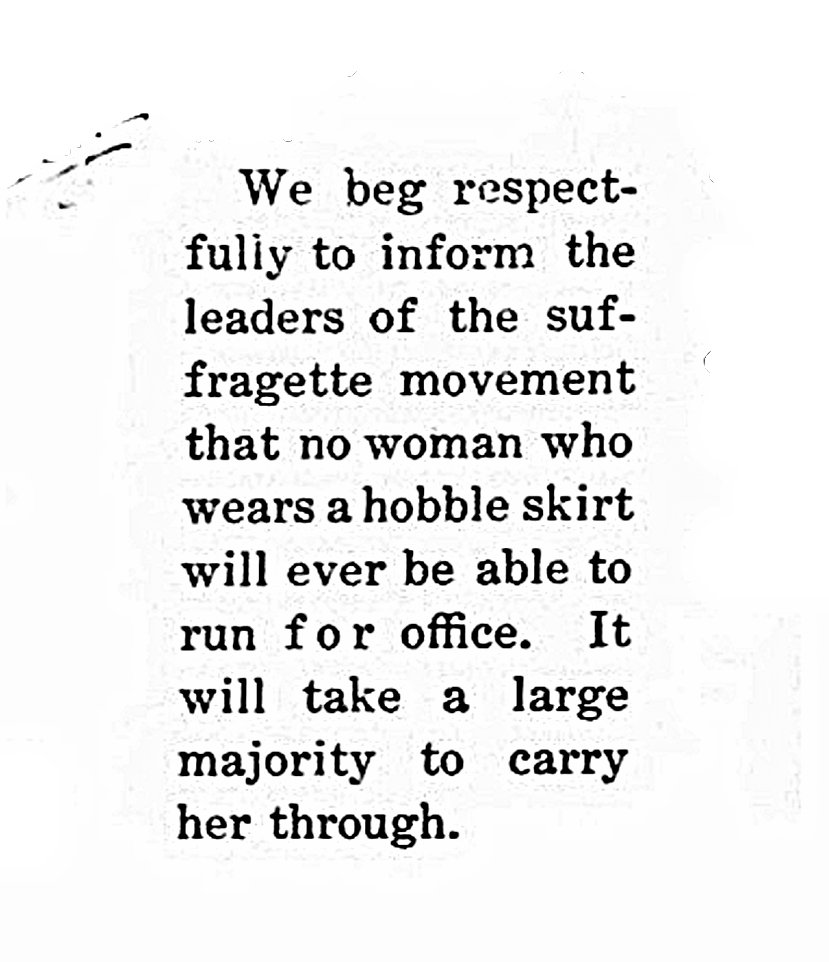

Excerpt from an article in Judge Magazine, November 11, 1910.

The writing humorously critiques both the fashion trends and the women's suffrage movement of the early 20th century. The hobble skirt was a popular style at the time, designed with a very narrow hem that restricted movement and made walking difficult. By saying that "no woman who wears a hobble skirt will ever be able to run for office," the quote plays on the double meaning of "run"—both physically running and campaigning for political office.

The line "it will take a large majority to carry her through" extends the political metaphor. In elections, a "large majority" is needed to win, but here it also suggests that a woman in a hobble skirt would literally need people to carry her because she can't walk easily.

This quip highlights the irony of women striving for political freedom while fashion simultaneously imposes physical limitations on them. It reflects on how societal expectations and trends can hinder progress, even as movements like suffrage aim to advance women's rights.

Take, for instance, the satirical verses published in magazines that depicted husbands chuckling at their wives' inability to storm off in a huff while wearing a hobble skirt. One could almost hear the collective sigh of patriarchal relief as women exchanged their once-free-flowing skirts for something that physically restricted them. This fashion choice, which many saw as both absurd and delightful, became a symbol of the tension between the avant-garde fashion world and the burgeoning women’s rights movement. While some women embraced the hobble skirt as a bold fashion statement, others criticized it as yet another form of societal constraint, both literally and metaphorically.

Drawing in Life Magazine, February 1910.

The image of two women wearing hobble skirts gazing at a museum painting of a woman (Princess Marie Adélaïde de France) in a large, flowing early 17th c. costume creates a striking contrast between different eras of fashion. The hobble skirt, popular in the early 20th century, was known for its narrow hem that restricted walking, symbolizing the societal constraints placed on women at the time. The Victorian gown in the painting, with its expansive layers and elaborate design, represents another period where fashion dictated a woman's mobility and status.

This scene highlights how fashion across different eras has both reflected and imposed limitations on women's freedom. The women in hobble skirts may see a connection between their own restrictive attire and that of the woman in the painting, prompting reflections on the recurring theme of constraint in women's fashion. The juxtaposition invites a commentary on how societal expectations continue to shape and sometimes inhibit women's roles and expressions, despite the passage of time.

Yet, the hobble skirt wasn't just a piece of clothing—it was an artistic canvas. Poiret, always the showman, ensured that despite its impracticality, the hobble skirt was a feast for the eyes. The skirt often featured intricate pleats, draping, and elaborate trimmings, turning its wearer into a walking work of art, albeit one with a somewhat restricted gait. Fashion magazines of the time showcased these designs with enthusiasm, and soon enough, the hobble skirt became a staple of high society wardrobes, though its reign was relatively short-lived, lasting only about seven years before women collectively decided they preferred to move a bit more freely.

The Straight Silhouette-Via the Tunic and Eton Line. Fashion Editorial in McCall’s Magazine for May 1918.

When comparing the early hobble skirt to the 1918 styles that followed, notice that these later styles continued to feature a straight hemline, much like the hobble skirt itself. The dresses of 1918, while less restrictive, maintained a straight and narrow silhouette that mirrored the earlier design. This style, known as the tunic, was becoming a fashionable garment during this period and influenced the evolution of women's fashion. Both the hobble skirt and the dresses of 1918 emphasized a vertical line, creating an elegant and elongated appearance. You can see similarities particularly in the way the garments shape the figure. Despite the differences in volume—the 1918 dress being more flowing—the overall effect of grace and sophistication is present in both.

In fashion, references to the "Eton line" often signify a classic, tailored, and formal style characterized by clean lines and crisp details. Therefore, the "Eton line" represents a design aesthetic that emphasizes structured tailoring, vertical lines, and refined elegance inspired by traditional Victorian and Edwardian garments. These parallels highlight how fashion often revisits and reinterprets previous styles, blending the old with the new.

In retrospect, the hobble skirt serves as a fascinating case study in the history of fashion. It highlights the paradox of women’s fashion in the Edwardian era—a time when clothing was used to both celebrate and constrain the female form. It also underscores the complex relationship between style, functionality, and societal norms. The hobble skirt may have been a joke to some, but it was also a symbol of the era’s broader cultural dynamics, illustrating how fashion could be both a form of self-expression and a tool for social commentary. As we look back on this peculiar fashion trend, one can't help but wonder: was the hobble skirt a step forward in fashion, or a fashionable step backward in the fight for women's freedom? Perhaps it's a bit of both—a fashionable paradox that continues to intrigue and amuse us today.

April Showers Bring May Showers. Editorial in Life Magazine, March 3, 1911.

The Hobble Skirt is characterized by its extremely narrow hem that restricted a woman's stride, causing her to "hobble" as she walked. This restrictive design was both a statement of fashion and a symbol of the constraints imposed on women. Despite its impracticality, the hobble skirt gained popularity among fashionable women who embraced its avant-garde appeal. It exemplified the tension between fashion and functionality, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable attire.